Read the actual story of how Dennis Etcheverry rescued a green 1970 Triumph TR6R from the clutches of a strange and sketchy individual.

1970 Triumph TR6R

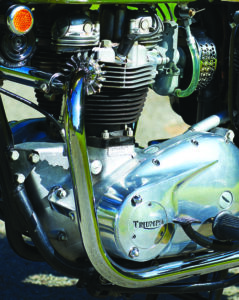

- Engine: 649cc air-cooled 4-stroke vertical twin, 71mm x 82mm bore and stroke, 9:1 compression ratio, 43hp at 6,500rpm

The knights, resplendent in shining armor (they spend eight hours a week polishing) dismounted and walked to the door of the shabby warehouse. Knocking loudly on the door, they shouted they were there for The Avocado. The door was opened a crack, and a beady eye was seen. “Whaddya want,” a voice snarled. The first knight stuck a mailed foot in the opening. “We are here for the Avocado,” he repeated loudly.

Enough of Dungeons and Dragons. The actual story of how Dennis Etcheverry rescued a green 1970 Triumph TR6R from the clutches of a strange and sketchy individual is entertaining enough.

Dennis is a master welder who is a partner in Norman Racing, a service facility for high-end sports cars. After hours, he collects motorcycles, mostly British. Even if he is not actively interested in buying, Dennis likes to look at the motorcycles for sale advertised in Craigslist. Some five or six years ago, Dennis was idly scanning the Craigslist ads. He saw a green 1970 Triumph that looked promising, and called the number listed in the ad.

A TR6R is a single carburetor version of the Triumph twin. “When I was a kid,” says Dennis, “Everyone wanted a Bonneville, the dual-carb twin with splayed intake ports. But the single-carb machines are much easier to maintain. There’s no carburetor synching. People who bought them used them for transportation, not racing, so when you do find a single-carb Triumph, it is less likely to have a worn out engine.”

Dennis says that the 1970 Triumph twins were “the last of the good ones.” Triumph motorcycles had become popular in the United States after World War II, and the British firm increasingly geared its offerings to the U.S. market, which bought style, chrome and horsepower, unlike the English, who wanted fuel economy and weather protection. Triumphs were sought after for desert racing in the Western states, and getting around and general mayhem everywhere else. In the 1950s, Triumph put out a quality product: warranty claims were low.

Triumph motorcycles find success stateside

The ancestor of the TR6 was the 650cc Tiger 110, introduced in 1954. It had swingarm rear suspension, a beefed up bottom end, a racing camshaft, and could top 100mph. It was followed in 1956 by the first of the TR6s, (sometimes known as the Trophy-Bird), which had an alloy head, a slimmer gas tank, a shorter seat, a wider rear tire and a waterproof Lucas magneto. This bike was aimed squarely at the Western desert campaigner, at a time where if you weren’t riding a Triumph in the hare and hound, you were not serious. Triumph started making East Coast models for enduro competition and wetter conditions and West Coast models for desert racing and drier conditions. As the Fifties progressed, most models got an easier to tune and more reliable Monobloc carburetor. Triumph also introduced tanks with stylish two-tone paint jobs. The TR6 came in two versions: a roadburner with low pipes, and a scrambler with high pipes, which were sometimes joined by an offroad competition weapon with no lights and straight pipes.

By 1957, Triumph was selling 13 different models in the U.S. In 1958, Triumph outsold all other motorcycle manufacturers in the U.S. To put this in perspective, nobody was selling a lot of motorcycles — Harley-Davidson only sold 12,676 that year — but Triumph dealers were doing better than most.

Honda comes to America

At this point, Honda entered the U.S. market, just as the first Baby Boomers reached driving age. Life completely changed for the U.S. motorcycle retailer. Honda had deep pockets as a result of its sales in Asia, and a number of other advantages. Honda’s company culture was to reinvest profits in the product, instead of distributing them to stockholders, as did Triumph. Honda had a great deal more leverage over its suppliers than Triumph, who was treated as a sort of a stepchild by Lucas and other companies whose largest customers were automobile manufacturers. As a result, Hondas were built on state of the art machinery, and had bright lights, electric starters and no leaks. Honda could build 1,000 lightweights a day, while maintaining quality control standards. Honda also spent a lot of money on general interest advertising.

At first, the appearance of Honda, and then Suzuki, Yamaha, and Kawasaki, improved life for the American Triumph dealer. For the first time since the 1920s, motorcycling became socially acceptable. Small Hondas were easier to ride and maintain than the Triumph Cubs that had been the entry level motorcycle sold by Triumph. Many retailers started selling both Hondas and a British make, such as Triumph or BSA. Riders would start on a small Japanese motorcycle and graduate to a larger British twin. Triumph sales boomed. In the 1960s, America’s Triumphs made the grids of flat track races and road races, got their owners to work and school and went cow trailing and touring.

Triumph soldiers on with the 1970 Triumph TR6R

The situation was different in England, where motorcycles had been used for decades as a cheap car substitute. With the advent of inexpensive small cars and Japanese imports, the get to work rider switched from the home product to either a four-wheeler or a two-wheeled import. As the Sixties progressed, Triumph pruned its offerings to concentrate on what it thought would sell in its overseas markets, the largest of which was the U.S. However, it did not upgrade its machine tooling, which limited what could be produced. Over the decade, management began to change from people who knew and understood motorcycles to people who knew nothing of either bikes or the people who rode them. Management and labor became increasingly antagonistic.

Cycle World arranged a test of a TR6SC in 1965. The magazine was enthusiastic about the power generated by the bike (45hp @ 6,500rpm). The bike came without a headlight, but with stiff suspension and long travel forks. Muffler-free pipes exited above the rear axles. In 1963, Triumph had gone to unit construction of engine and gearbox, which Cycle World liked because there were fewer joints to leak, and its report noted the fact that the test bike stayed leak free in 600 miles of hard desert riding. Testers praised the TR6SC’s ease of starting and ease of shifting. “But what we liked most about the Triumph special is that it is such fantastic fun to ride.”

Three years later, Cycle reported on the road going version of the TR6, the TR6R. Although the single-carburetor machine was not the beast to beat in drag races, testers stated that it was the most manageable and the most durable of the Triumph twins. Testers did not like the new Concentric carburetor and suggested it be replaced by either a Monobloc (the previous edition of the Amal) or a 30mm Japanese instrument. They did like the strong but light frame, the good handling and the double-leading-shoe 8-inch drum front brake with an air scoop.

1969 marked the debut of both the Honda 750, a powerful but well-mannered machine with a front disc brake and an electric starter, and the Kawasaki H1, a screaming 500cc 2-stroke, nicknamed “The Widowmaker.” Triumph had a triple-cylinder design ready to go in late 1963, but dallied around with styling changes and corporate inertia. Triumph was selling more bikes than ever — about 28,700 in 1967 — but failed to pay attention to quality control. Tooling was run until completely worn out. Warranty claims mounted.

Cycle revisited the TR6R in 1970. Its report on the 1970 TR6R was, in the main, positive. The starting was as easy as it had been in 1965, and the bike stood up to side winds, had almost no noticeable vibration up to 70mph, and was a pleasure to ride on twisty roads and around town. Over 70mph, the engine transmitted vibration through the seat, although rubber mountings on the bars quelled the tingle to the fingers. The tester commented that the taillight stopped working during the ride and there was a small leak. The color was Spring Gold, “a translucent avocado green.”

Last year before big changes for Triumph

1970 was the last year for the desert-racing-proven frame. The parent company in England had spent millions of dollars on an R&D center staffed by non-motorcyclists, who designed a new, and very tall frame and changed the look of the Triumph twins. Customers did not like the look of the 1971 Triumphs, and objected to the excessively high frame. No one had checked to make sure that the engine components would fit in the frame, resulting in a hasty redesign and delays in getting bikes to dealers.

The 1970 Triumph TR6R is therefore of interest to people who want to actually ride their vintage machines, like Dennis, which is why he followed up on the ad. There was only an answering machine on the other end when Dennis called. A day passed with no return call. Dennis mentioned the Avocado, as he began to think of the bike, to his friend Scott, who runs a motorcycle dealership by day and also collects Triumphs by night. Scott called, also got the answering machine, and left a message with the shop number.

The person whose phone was listed as the callback number called the shop, and got Scott’s wife, Juliana. “Oh s@#$, another Triumph!” (She is actually a good sport about Scott’s Triumph habit.) Juliana passed the phone over and Scott and Dennis made plans to see the bike, although the person on the other end sounded more than a little weird. The address was not in the best part of town.

The adventure for the Triumph TR6R begins

Scott and Dennis showed up to find the bike in a damp garage. They were glad they had decided to go together. The hairy and greasy person showing the bike (who turned out to not be the owner) was the sort of person who, if there is more than one in a bar, any thinking person backs out slowly. The actual owner was the mother of the girlfriend of the person showing the bike. Mr. Greasy was trying to ingratiate himself with Girlfriend’s family, who was not too thrilled about Girlfriend being seen with this guy, and was going to be a hero by selling the bike for the family. Problem was, he didn’t know the first thing about Triumphs, and couldn’t even start it.

The bike itself, however, made up for the seriously weird person who was trying to sell it. It was absolutely 100% original. The paint and bodywork looked strangely dull, which on investigation turned out to be due to a quarter-inch-thick coat of paste wax all over the chrome and paintwork. The paint and chrome under the wax was absolutely perfect. There was no rust anywhere. Dennis was able to start the Triumph on the third kick. It sounded wonderful. It had the original license plates from 1970.

One special item on the 1970 Triumphs was the taillight extension. The U.S. Department of Transportation decreed in late 1969 or early 1970 that motorcycle taillights had to extend beyond the end of the fender. Honda spent millions to reengineer the taillight assembly and fender. Triumph simply designed an extension for the taillight. This TR6R has the original (and rare) taillight extension, increasing the value of the bike.

Scott and Dennis opened negotiations. The sketchy seller seemed uncertain if he even wanted to sell the bike at all. The conversation went back and forth for a while. Finally, Scott lost patience. “Look,” he said. “We have a ramp, tie-downs, a truck and CASH. And we are not coming back.”

At this point, Mr. Greasy realized that Girlfriend’s family would be furious if he botched the deal, took the cash and handed the bike and its pink slip over. Dennis and Scott loaded the Triumph as fast as possible, jumped in the truck and ran.

Even better news for the Avocado

A couple of days later, Girlfriend’s mother called. She ranted for a couple of minutes about how she disliked Sketchy Boyfriend, and stated she was happy that the Triumph had gone to someone who would care for it. The bike had belonged to her father, now passed, who kept the bike in his living room and waxed it when he had nothing else to do. As he got older, his eyesight got worse, which explains why the bike was covered with paste wax. Girlfriend’s mother had the complete service records and was happy to send them over.

Meanwhile, Dennis went over his new prize. It took two days to get all the wax off. The bike needed tires, fuel lines and a change of oil. Under the wax, the bike was perfect. The service records arrived, with the original bill of sale. Per the sales records, in 1970, the cost to finance a motorcycle was 16-18%. (Think about that when you complain about financing charges!) The last service on the bike was 40 miles before it was parked.

“It’s a very simple bike,” says Dennis. “Once you get the drill down, you can start the TR6R on the first or second kick. It needs premium gas. You turn on the gas, free the clutch, give it half choke and kick. The carb does not go out of tune. Change the oil every thousand miles. Parts availability is better than it was 20 years ago — Bloor (owner of the modern Triumph factory) sold the tooling to the right people.”

“The Avocado gets ridden a little bit — I have a lot of bikes — but what I mostly do with it is take it to shows. It has won at a lot of shows. No one believes it is that original.” MC

1970 Triumph Bonneville

In 1970, if you were the typical Triumph fanatic eyeing the latest and greatest from the Meriden factory, you would probably have walked right past the TR6R featured here and gone for the Bonnevilles. The twin-carb setup was originally an accessory offering, but when the splayed port head kits sold out, Triumph decided to incorporate the new head in a new model. The first T120 Bonnevilles appeared in 1959 and quickly became wildly popular Stateside. The 1970 model Bonneville was good for more ponies (46 horsepower vs. 43 horsepower) and more top speed (108mph vs. 103mph) than the single-carb machine, and those with a need for speed overlooked the extra maintenance. “When I was a kid,” says Dennis Etcheverry, “Everyone wanted a Bonneville.” Bonneville lust has not gone away with the years, and the market for a classic Bonnie in good shape continues to be strong.

Shortly after he acquired the Avocado, Dennis’ friend Scott found this unrestored and very original 1970 Bonneville in Oregon. The prior owner had used the bike as a template for a restoration, then decided to sell both the unrestored and restored machines. Another friend wanted the restored bike, and Dennis ended up with the Bonneville.

Dennis has been taking the two bikes to shows, enjoying the reactions of admirers. “No one can believe that both bikes are unrestored!

Originally published as “The Rescue of the Avocado” in the September/October 2023 issue of Motorcycle Classics magazine.