Kenny Roberts’ 1975 Indianapolis Mile win remains a race of historic proportion.

During the evening of Aug. 23, 1975, KR wrestled to victory circle one of the most unorthodox dirt track race bikes ever, a flat tracker powered by a 120-horsepower Yamaha TZ750 inline 4-cylinder, liquid-cooled, 2-stroke engine originally developed for road racing. But for 24 and nine-tenths laps the race appeared futile for Roberts. After starting from the back row he ultimately overtook race leaders Corky Keener and Jay Springsteen on the final go-round, nipping them by inches at the finish line. It was the only time KR led the race that otherwise seemed a lost cause for the defending two-time Grand National Champion. Readers unfamiliar with that race are encouraged to set this issue of Motorcycle Classics magazine down right now so you can search YouTube to view the historic video footage of Kenny Roberts’ Indy Mile. At the video’s conclusion report back ASAP because, boy oh boy, do we have another tall tale to tell you.

Amid the Indy Mile’s post-race celebration, AMA historians quickly noted that this was the first time a 2-stroke engine with more than two cylinders had powered its way to win an AMA Grand National Championship dirt track race, in this case the much ballyhooed Indy Mile. That night history was made … sorta.

Sorta because a month and a half prior, July 6 to be precise, another multi-cylinder 2-stroker had already won an AMA Regional flat track race, the Stockton Mile in California. The winner of that non-National event was 21-year-old Scott Brelsford, riding the No. 19 green monster featured here. The bike, built by still-aspiring tuner Erv Kanemoto and powered by a Kawasaki H2R 750cc 3-cylinder air-cooled 2-stroke engine, now belongs to collector Mike Iannuccilli. It remains the first multi-cylinder 2-stroke to win a major AMA flat track race. Ever.

Even though the Stockton Mile wasn’t a National points race, its Regional Championship status made it significant on the race calendar, attracting many of the top Expert-ranked AMA stars of the time, including Rex Beauchamp, Jim Rice, and former GN Champions Mert Lawwill and Gene Romero, among others. They were there to compete for Regional points and, more importantly, for cash. The AMA promoted Regional races throughout the country, and those isolated races often served as potential feeding grounds for pro riders to earn extra money during the long racing season.

Kanemoto finds success with Kawasaki H2R engines

Unlike KR’s success with his TZ750-powered beast (Roberts had not ridden the bike until Indy), Brelsford’s win didn’t happen overnight. Indeed, up to the Stockton Mile this type of flat track racer was unproven and equally untested by its creator and owner Kanemoto, among the most talented and innovative race-bike tuners of his time. Moreover, Kanemoto’s entry wasn’t factory-backed, as was Roberts’ TZ-powered racer. Interestingly, though, as we shall see, both bikes shared similar frames, differing mainly in the placement of their motor-mounts and other proprietary fixture locations … and, of course, their engines.

Like Yamaha’s TZ750, the Kawasaki H2R displaced 750cc. Unlike the TZ750, which Yamaha developed specifically for road racing, the H2R engine was a modified version of Kawasaki’s road-going H2 engine (Mach IV). Even so, the H2R was no slouch, and had powered two-time AMA Grand National Champion Gary Nixon to three AMA National road race wins in 1973, the most by any rider that year, qualifying him as AMA’s 1973 Road Race Champion. Even so, Kawasaki opted not to support Nixon and Kanemoto for 1974, prompting the tuner and rider to sign contracts with Suzuki for the 1974 season. They would use Suzuki’s GT-based liquid-cooled 750cc triple for their 1974 AMA road race endeavors. What to do with the pair of proven Kawi engines that now belonged to Kanemoto?

Nixon came up with a plan, suggesting that his wizard tuner shoehorn an engine into a flat tracker frame so the duo could also compete in AMA’s Grand National dirt track circuit as well (read: racing for more cash). One daunting question remained: where to find a frame for the wide 3-cylinder engine and its trio of bulbous expansion chambers?

Kanemoto gave a devilish smile; he had a friend who he had worked with in the service department at East Bay Yamaha years before. That friend, Doug Schwerma, now had his own race-frame business, Champion Frames. And it just so happened that Schwerma had recently put together a frame for a similar project, shoehorning a massive Honda CB-750 Four engine into a frame of his own making. According to sources of the time the Honda project had been commissioned by American Honda, with hopes of joining the AMA’s annual flat track feeding frenzy known as the Grand National Championship. Even though the Honda connection was quickly terminated, Champion Frames eventually built frames to cradle the Kawasaki and Yamaha 2-strokes. Most insiders consider those frames’ basic geometry and related dimensions were based on existing race frames that Schwerma’s company built to cradle small-bore 2-stroke engines for short track racing, and to cradle Yamaha’s 4-stroke 650/750 twin. Those frames had proper rake and trail specifications that, along with proper wheelbase and engine placement, created a balanced formula for sliding around hard-pack dirt ovals.

After listening to Kanemoto’s proposal-cum-request, Schwerma took delivery of the H2R engine cases, using them to relocate the frame jig’s motor mount points to suit the Kawasaki engine’s footprint. He also altered a few other dimensions here and there, and presto — the racing world was treated to a 2-stroke triple for America’s flat tracks. In the process Nixon, who had been absent on hard-pack ovals after Triumph downsized its U.S. race program in 1972, regained the itch to “do it in the dirt.”

As it turned out, Nixon’s first experience with the new Kawasaki “framer” at the September 1974 San Jose Mile, plus an injury suffered while testing the Suzuki in Japan, prompted him to rethink matters. Brelsford (1973’s AMA Rookie of the Year who had recently ended his tumultuous and short-lived relationship with Harley-Davidson’s factory team) would replace Nixon as rider for the new Kawasaki slider. The combination of Kanemoto’s tuning talent, a powerful engine that benefitted from such talent, and a youthful and aggressive rider, spelled potential trouble for the horde of Harley riders and their XR750 motorcycles that dominated flat track racing at the time.

Moooove over, here comes the Kaw

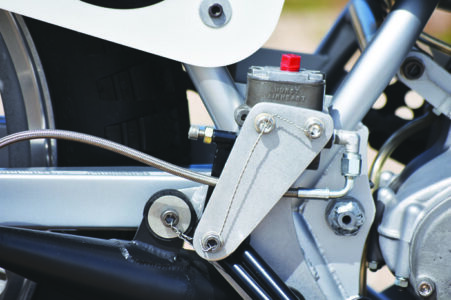

By summer of 1974 Schwerma delivered a frame and swingarm, plus peripheral parts such as a seat, gas tank and such to Kanemoto, who immediately began piecing his new puzzle together. The completed project included typical mainstay wares as a Ceriani fork up front and a pair of Boge rear shock absorbers. Also, Kanemoto modified a set of the factory H2R road race exhaust chambers so that all three gathered along the bike’s right side; oval track sliders only turn left so cornering clearance on that side of the bike is paramount, thus all exhaust pipes merged to the right side.

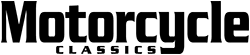

Howard Barnes laced the brakeless front hub to a 19-inch rim, and he fitted the 19-inch Morris magnesium rear wheel with a disc brake and Airheart caliper that, in Kanemoto’s words, was “similar to the small units on the go-karts I used to race and tune.” (Time out for additional background on tuning wizard Erv Kanemoto: His father had raced speed boats powered by 2-stroke engines, and that’s where the now-famous motorcycle tuner cut his tuning teeth; he later took his talents and tools to the go-karting arena where he furthered his skills with oil-burning engines that he later applied to road race motorcycles. Okay, end of time out, and all featured players in this story, back to your positions so that we can complete this historic saga!)

In his usual manner the crafty tuner wasted no time sorting through the parts for assembly, finishing shortly before the San Jose Mile in September 1974. With Nixon still the designated rider, the pair set out for practice and qualifying at the fabled Mile track. Various teething problems prevented Nixon from transferring to the Main, but based on what was learned that day, he deemed the bike needed a longer wheelbase so the big Kaw would be easier and more predictable to turn and slide, important traits when competing on a mile-long oval track where speed is measured in the 120mph range. According to Cycle magazine, during the winter Kanemoto extended the swing arm and moved the rear shocks’ mounting points about 3 inches forward, plus Schwerma and crew fabricated a new saddle-type engine mount to further secure the engine’s front portion to counter vibration. In the interest of rider comfort, Kanemoto also rubber mounted the handlebars.

Nixon’s prognosis was confirmed a short time later when Kanemoto, now with Brelsford in the saddle, headed to another local flat track race, this one across the bay at Golden Gate Fields near Albany, California. Years later, Brelsford reflected on his first track session with the bike, recalling, “You had to spin it [the engine’s revs].” And when you did? “You went fast.” How fast? “It could spin the rear tire the entire length of the straights,” answered Brelsford, as calmly as if describing how he rolled the bike into the garage for the night. Eventually projected top speed was about 140mph, give or take. By comparison, Harley-Davidson XR750s peaked at about 120mph on a Mile oval. Ironically, at one point Brelsford and Kanemoto thought that the engine’s clutch was slipping (it always showed signs of “creep” at the starting line), but after further examination both men determined that between excess power and unsophisticated tire technology of the time, the rear tire was breaking loose when maximum horsepower kicked in!

The brash Brelsford gave additional insight about riding the monster: “You also had to downshift for the turns.” Huh? On a Mile track, downshift? He explained that, doing so, “the rear tire could spin [slide] through the turn” as it should on any flat tracker to maintain the mysterious gyro effect needed for sliding a motorcycle at those speeds. And because the 3-cylinder engine didn’t produce much torque, you had to initiate rear wheel spin before entering the turn by downshifting to a lower gear. Otherwise, the 2-stroke engine’s explosive power wanted to send the rear wheel into a tizzy, prompting it to wildly loop around until it became the bike’s front wheel. And when that happens you don’t need to be Albert Einstein to figure out that you had just violated a major law of physics.

And so Mr. Brelsford mastered the art of downshifting his new ride, and in the process he laid down some rather impressive lap times on Golden Gate Fields’ rather loose surface … until the carburetor slides began to stick. Result: DNF, and back to the shop for some additional Kanemoto magic in preparation for the May 1975 San Jose Mile. Furthermore, during the subsequent mild California winter, Schwerma’s second chassis arrived at the Kanemoto residence for another bike that Kanemoto wanted to put on the track. Local racer Donnie Castro, who had recently been released by Team Yamaha, was assigned the second bike. Kanemoto’s logic suggested that two bikes would gather twice as much track data as could a single bike. The team was growing in size and gaining strength on the track.

1974 Kawasaki H2R Flat Tracker makes it to San Jose

To say that Brelsford was fired up for the upcoming San Jose race is an understatement. He was on a mission, and rather quickly it became apparent that he was, indeed, a force to be reckoned with. Every Expert-class rider, including Mert Lawwill, who had perhaps the fastest XR750 in the field, took notice. Brelsford and Kanemoto were about to show who wielded the real horsepower. Matched against Lawwill in the second transfer heat race, Brelsford caught fire after the field spread out, giving him a clear path to use his bike’s top speed.

As Art Friedman reported for Cycle Guide magazine, Brelsford “overtook bikes on the straights in clumps of two or three.” The H2R 2-stroke’s banshee-like howl was equally matched by its rear tire spin on San Jose’s long and inviting straights. Amazing, and after a poor start Brelsford closed on Lawwill to finish second in their transfer heat. Brelsford was fired up for the Main, and Cycle magazine’s race report made it clear: “Brelsford was flared-nostril enthusiastic, having qualified the bike a fine tenth-fastest.” Brelsford’s Kawasaki was equally as fast as the Harleys, but, as Cycle‘s report stated, “the only capable threat to the H-Ds sputtered out of the race and into the pits with one of its air cleaners adrift, a cylinder full of dirt, and a connecting rod trying to create a new alloy with the crankpin.”

Even so, the San Jose crowd watched in wide-eyed disbelief as Brelsford leap frogged from eighth to fourth, then to third before engine trouble sidelined him. There’s always the next race, and in reality the “next race” was to become The Race for the feisty privateer team. Next stop, Stockton.

Go for the California gold

By that time Kanemoto was able to “upgrade” the Kawi’s tires, replacing the narrow Dunlops with a Pirelli 19-incher up front and a Carlisle 4.50 x 19-inch hoop on the rear. Even so, sliding traction remained elusive, so Brelsford did all he could to keep the bike upright when corner sliding. He also had gained more confidence since riding it at San Jose, years later stating that “it was fun to race the thing, but it was a challenge.” It turned out, too, that he was up to the challenge, and the young, brash Brelsford pretty much owned the race at Stockton, becoming the first rider to ever win a Mile race aboard a multi-cylinder 2-stroke framer. But had the race gone another lap, Brelsford would have DNFed; the bike’s chain came off during the cool-off lap!

Even so, history had been made, and then it was on to Indianapolis where Brelsford qualified high enough to earn a front-row starting position for the Main. Roberts dutifully lined up on the back row. When the green flag fell to start the race, Brelsford got a worthy start, but by the end of the first lap something snapped in the engine, terminating his ride. His teammate Castro had failed to qualify for the Main, but the team decided to continue racing through the remainder of the 1975 season.

Brelsford seemed to adapt better to the H2R’s brute power, but neither rider met with any noticeable success after the Stockton win. They competed at Syracuse but both failed to transfer to the Main before heading back to the West Coast for the season’s second San Jose Mile.

As the weekend progressed Brelsford was feeling chipper until a wayward countershaft sprocket during practice prompted the bike to stand up and veer toward the outer fence — at about 100mph. “That one got to me. I was trying all I could not to hit the fence!” He avoided that catastrophe, but that pretty much ended the saga of the feisty team.

Recalls Kanemoto, “Looking back at the bike that Donnie [Castro] rode, I set it up hoping to reduce wheel spin for better traction exiting the corners. In reality that set-up probably made it harder for Donnie to complete the corner under heavy throttle, which resulted in less wheel spin, making it harder for him to complete the corner. That probably forced him to not open the throttle as early or hard as he preferred. With that setup, he more than likely would have ended up chasing the front (wheel). It’s one more thing I think about over the years, that I wish I could go back to that time to correct it for him.”

AMA Banned bikes

But none of that was to be. A decision by the AMA rules committee following the 1975 racing season secured that fate of the big Kawasaki and Yamaha. Before the winter meetings adjourned, the AMA banned multi-cylinder 2-strokes from flat track National competition. Perhaps Roberts’ famous quote concerning his TZ750 monster, “They don’t pay me enough to ride that thing,” sealed the fate. Or maybe, as insiders suggest, banning the 2-strokes was part of a compromise that also led to the formation of a separate AMA road race championship (where purists said the 2-stroke multis belonged!). In any case, and racing politics aside, the summer of 1975 witnessed two motorcycles powered by multi-cylinder 2-stroke engines etch their respective marks in motorcycle racing lore.

And what became of those milestone milers? Fortunately — even surprisingly — most of them survived, and the Brelsford bike even found its way into other racing arenas, thanks in part to Dennis Zickrick of Fort Collins, Colorado. A few years later Zickrick had acquired the Brelsford bike, giving it new life. Eventually Zickrick entered it in the annual Pike’s Peak Hillclimb where he and the old Kawi set a new path towards making even more history! Their historic path led to the top of Pike’s Peak when Zickrick and his bike became, possibly, the first multi-cylinder 2-stroke framer to reach the clouds.

“I finished in the top 10,” Zickrick recalls with certain pride. “A Honda rider crashed and blocked one of the turns, so that forced me to slow down enough to be ninth.” Still, a credible finish. And that raises another interesting sidebar to this tale: In 1980 Zickrick became a member of American Honda’s Superbike team, and was responsible for maintaining future world champion Freddie Spencer’s Honda CB750-based Superbike. A couple years later Kanemoto’s tuning talents were pressed into service to help Spencer win his three Grand Prix World Championships for Honda. Yeah, small world.

Zickrick continued racing the old Kawi, occasionally competing at local outlaw half-mile tracks until the Pike’s Peak Museum invited him to display the legendary bike as one of the events’ more interesting entries. Zickrick figures that he owned the bike for about 30 years before selling it. “But I don’t remember to who,” he adds. Eventually Dan Masachini acquired it, but he soon sold the Brelsford bike to Kawasaki Triple collector Jergen Weiss in Germany. As a member of the European-based H2 Club, Weiss tinkered with it, occasionally revealing the framer at motorcycle events before selling it to collector Mike Iannuccilli who, as he patiently does with the historic racers in his collection, set about returning the bike to its former glory.

“I like to restore my bikes to look exactly the way they raced years ago,” says Mike. “These are historic pieces,” he adds, and by “exactly” he means a mirror image of the bike’s original livery, right down to paint scheme, decal placement, you name it. And that’s what he did with the Brelsford bike and the Castro bike that he later acquired. Historic moments happen only once — that is why they’re historic. And historic best describes these two Kawasakis, built nearly 50 years ago by a historic tuner, to be raced by three of the many historic men to have populated the starting grids of America’s historic flat tracks. MC

Originally published as “Kanemoto Dragon” in the September/October 2023 issue of Motorcycle Classics magazine.