Drive into hodaka motorcycle history and the world of Japanese small classic dirt bikes.

In the world of classic dirt bikes, Hodaka motorcycles aren’t your average bikes. In many cases, a vintage motorcycle is Dad’s Toy. “Don’t bother your father, he works hard and needs some time to himself,” explains Mom. Hodaka motorcycles are a little different. Small, light, user friendly and easy to start, Hodakas tend to be Our Family Toy. Mom, Dad, Junior and Sister ride, Grandma cornerworks and Grandpa wrenches. Hodakas are a reason for a family social outing. Hodakas are weekend fun for all.

The dirt on Hodaka motorcycles

The Hodaka phenomenon of the 1960s and 1970s was caused by a unique sequence of events. The Baby Boom generation was then in their teens, there were a lot of unpaved roads in rural areas and Honda had popularized riding small motorcycles.

Following Honda’s success, many Japanese motorcycle companies sought to export their products to the United States. Yamaguchi, one of Japan’s oldest motorcycle companies, with roots back to 1941, was one such company. At the same time, Pacific Basin Trading Company (PABATCO), then a subsidiary of Farm Chemicals of Oregon, was looking to trade Oregon farm products for goods from other countries. PABATCO was headquartered in Athena, a little town in northeastern Oregon just north of Pendleton.

Starting about 1961, PABATCO began importing Yamaguchi motorcycles, first in 49cc and later in 80cc versions, and these proved quite profitable for the Oregon-based company. But the fierce competition between Japanese motorcycle companies in the early Sixties hit the smaller companies hard, and Yamaguchi went under in 1963. The last engine used by Yamaguchi was an 80cc three-speed made by Hodaka, a Japanese builder of two-stroke engines.

With their most profitable item no longer available, yet with dealers in place and strong demand for small motorcycles, Harry “Hank” Koepke, Adolph Schwartz and other PABATCO employees decided to collaborate in designing a motorcycle for the U.S. market. And with Hodaka already in place to supply engines, they looked to Hodaka to build their new bike. Rumor has it that much of the initial sketching was done at the local Green Lantern Tavern, with the help of a few cocktails.

Styling cues for the planned bike were taken from the Cotton, a British-made offroad competition machine with a record of success in offroad racing. The Cotton made heavy use of triangulation to stiffen the frame, and the PABATCO prototype adopted this idea. The all aluminum alloy engine would be based on the two-stroke, piston-port single used in the last Yamaguchi, but with a little more cubic capacity and one more gear, giving it four speeds instead of three.

The crew built and tested a prototype on the trails surrounding Athena. Blueprints in hand and satisfied they had something to work with, Hank went to Japan and hammered out contracts with suppliers, Hodaka chief among them, as the company would not only supply the engine for the new bike but assemble it as well. Hodaka agreed to grant PABATCO an exclusive distributorship for the new bike, and production began in 1964.

The Ace

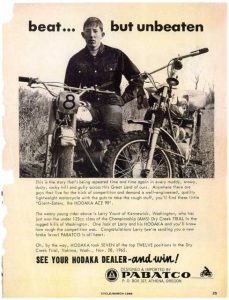

This first Hodaka, the Ace 90, set the tone for the new brand. The Hodaka Ace was fully street legal, but it was more than capable in the dirt. It had a light tubular steel frame, the exhaust was placed high and out of the way, and there was plenty of room under the fenders to shed mud.

At the time, there was almost no domestic competition to the Hodaka. Harley Davidson was also making two-stroke machines, but they were basically street bikes that had to be specially set up for offroad duties. And there certainly wasn’t much to look for from the other Japanese imports, most of which had heavy pressed-steel frames and weren’t designed for the dirt. The only real alternatives came from the British imports, which were much heavier and invariably required more maintenance.

Although it only had a shade over 8hp, the finished machine’s light weight (about 170lb) and good handling gave good performance, and thanks to the Hodaka engine it was easy to start and reliable. A contemporary ad celebrated two Hodaka Ace 90 riders making a run down the Baja Peninsula with no problems besides flat tires. And with a list of price of $379, the new Hodakas were an instant hit. “There was a feeling that these bikes were designed by people who actually rode them,” says Stewart Ingram, who races a Hodaka Super Combat in the American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association (AHRMA) motocross series and has a collection of Hodakas.

From almost the beginning, dirt bikers with a need for speed started fabricating parts and accessories for motocrossing the little bikes. Some people even made something of a living at it. Trials enthusiasts discovered the Ace, modifying it as needed for trials competition, while hare and hound and enduro enthusiasts fixed up the Ace for their needs.

As race parts became easily available, the Hodaka Ace was the basis for all sorts of offroad competitions. Ace 90s won their class in the 500-mile Greenhorn Enduro (held in the unforgiving mountains of Eastern California), the National Trail Bike Championship and the Pike’s Peak Hillclimb.

For the first few years Hodaka and PABATCO, unwilling to tinker with success, gave the Ace only minor upgrades: The taillight got brighter, and a trials type rear tire became standard equipment. Even so, over 17,000 were sold during the model’s four-year run. Bigger changes came in 1968 with the Ace 100, when the single-cylinder engine was enlarged to 98cc and maximum horsepower rose to 9.8 ponies at 7,500rpm. Hodaka also added another gear, for a total of five, and beefed up the rear shocks. Like the Ace 90, the Hodaka Ace 100 was fully street legal, but a hot performer offroad.

Hodaka sales continued to increase, and as they did Hodaka made engines available to frame builders, with engines sold to builders having an “E” after the serial number. In 1970, famed English frame builder Rickman made a beautiful chrome and blue offroad bike using the Hodaka engine. Stewart has one in his collection.

The name race

In 1969, Hodaka started making purpose built bikes for various forms of competition, giving them fun, wacky names that only added to their popularity. The first out of the gate was the Hodaka Super Rat, a motocross version of the Ace 100, and a bike that saw plenty of racing action. “You could win races with a Super Rat right out of the box,” Stewart says. 1972 saw the Wombat 125 and the appearance in ads of the Hodaka Wombat, Hodaka’s mascot and a happy beast wearing a helmet. 1973’s Dirt Squirt was designed as an offroad fun machine and advertised using cartoons featuring the world’s fastest clam, “Racer Clam.”

There was also the Hodaka Combat Wombat, the very fast Super Combat and a revised version of the Super Rat in 1974. However, by this time Hodaka was beginning to face serious competition from the larger Japanese motorcycle manufacturers, who had been taking serious notice of the burgeoning market for offroad bikes. Yamaha introduced the Yamaha DT-1 in 1968, and in 1973 Honda introduced the Honda Elsinore, its first serious offroader and a machine supposedly marketed under cost to ensure Honda’s grab at market share.

Struggling to keep its piece of the market, Hodaka started building 175s and 250s, including the Thunder Dog and the dual sport Road Toad (“The answer to ‘Wart’s new?'”), which Stewart says were a little heavy for serious offroad use. Sales, however, were falling. The market, a market Hodaka arguably created, was changing, and Hodaka was unable to keep up with the sophisticated R&D efforts of the Big Four.

The final blow came when Shell Oil, which had purchased Farm Chemicals, checked the books, decided that PABATCO was losing money and shut down the operation in 1978. It was fun while it lasted. Harry Taylor, head service manager, says his time at PABATCO was a 12-1/2-year paid holiday.

The faithful remain

Hodakas were something of a cult phenomenon even in their day, and they continue to amass a dedicated following. Ironically, not long after the demise of Hodaka, interest in vintage offroad competition started growing. While modern offroad machinery has awesome capabilities, unless you’re a young athlete many of the competitive dirt bikes made in the last 30 years are hard to ride. Hodakas, on the other hand, can be ridden by just about anybody.

Their enduring appeal is highlighted at Hodaka Days, which take place every year in Athena, and features motocrossing, offroad riding classes, bench racing and parts swapping — all featuring Hodakas, of course. And for 2006 the event was held in Ohio, where Hodaka was the featured offroad marque for the AMA’s Vintage Motorcycle Days at Mid Ohio racetrack.

“Hodaka has a special following,” Stewart says. “There’s this feeling of, ‘We’re the underdog! We’re Number Two, so we try harder! There’s nothing we can’t do!’ Hodaka people are down-to-earth and friendly, and there really is a wide spectrum of people interested in the bike. At Hodaka events, you see little kids with Hodaka coloring books, 13-year-olds racing and Harry Taylor, the former service manager explaining how to make a timing wheel out of a paper plate.

“There’s no attitude and a sense of humor about the whole thing. How can you be serious around bikes with names like Dirt Squirt and Road Toad?” MC

Resources:

• Hodaka Parts and Resources

• Hodaka Owners Group

• Hodaka Forum

• Hodaka Days

Read more about the motorcycles mentioned in this article:

• Randy Smith’s Hodaka Super Rat

• Yamaha DT-1